|

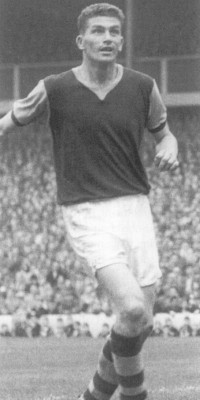

Tommy Cummings, Jimmy McIlroy and Jimmy Adamson were the senior pros but there was a younger group including myself, Jimmy Robson and John Angus, John Connelly and Ray Pointer who were given special attention. Harry just carried on with that, didn’t really change anything, he didn’t need to.

He and Alan Brown were different characters though. Alan was the Iron Man, strict on discipline, took no nonsense, if you got a rollicking from him you just felt like melting but at the same time there was a relaxed side to him when there needed to be. Alan once told us we had a plane to catch once at 7 in the morning for a summer tour abroad. But it wasn’t at 7 in the morning it was 7 at night. But all he did was have a laugh at himself when we got there and out came the cards.

Harry was different, there was a gentler, softer side to him; he didn’t need to shout or bully to get players to play for him. You wanted to win for him, not because of him. You’d never have called Harry the Iron Man. His philosophy was simple, and that was to go out and play, move forward, get onto the attack, and if the others scored we just had to score more than them. We didn’t shut up shop and go for a 1–0 win we just wanted to score as many as possible. That’s why there were so many high scoring games and why we came back and drew games like the 4–4 game at Spurs when we were losing 4–1 at halftime.

Several of us worked at Bank Hall Pit at the same time as playing football. That was instead of doing National Service – serving your time in the army, which is what everybody had to do until it was abolished sometime in the sixties. Tommy Cummings, John Angus, myself, John Connelly. Jimmy Robson all served our time there and it was about the same time as we won the championship, although by the time of the Championship we had stopped at the Pits. We worked at Bank Hall till 4.30 every day and then trained in the evenings. There were a few of us had to do that. Can you imagine that… we worked for the NCB all day, above ground, either as joiners, electricians or bricklayers and then played First Division football. Spurs players didn’t do that. That’s another reason why it was such an accomplishment for a small town team like Burnley to do so well. If there was a night game we got the afternoon off but then when I moved to Thorny Bank Pit there was an understanding manager there who gave me time off in return for tickets. It helped if the manager was a Burnley fan.

At Gawthorpe we didn’t spend hours looking at blackboards and discussing tactics. Harry took us through the opposition before a game, went through our responsibilities. But there was no need for tactics as such. You had eleven good players, they had their positions and formation, played to their strengths, and they went out to score goals. The team picked itself. Worry about you, not the opposition, is what he said. The tactic was simple - move forward and score. In training at the end of the day he loved the 5 a sides, loved to win. So no, we were never bogged down in theories.

In the dressing room he didn’t rant or rave, bully or shout. If he did it was a very rare occasion and it would soon pass if he lost his rag with one of us. If we were losing he didn’t need to lose his temper with us. But he did get himself worked up during a game and on a Saturday he was a very different chap to the weekday Harry Potts. Before a game he’d go through routines and free kicks, quietly remind people of their jobs. Let’s just say he had a way of getting you to respond without throwing teacups around. He didn’t need to. He’d certainly come in red faced and worked up at half time and sometimes full time. You could never say he was calm but most of the time on a matchday he kept himself under control.

There were a few games when you might have expected him to be angry but he wasn’t. We were beaten 6–1 at Wolves near the end of the Championship season but he didn’t raise a fuss. Truth is half a dozen of us had just had injections in preparation for the New York Summer tournament we were to be in. We had painful swellings under our arms, felt really ill, and me – I woke up after the afternoon sleep drenched in sweat feeling dreadful. No wonder we lost. The fans see you lose or hear the score and they don’t know the background to it. At Ipswich in a later season we were beaten 6–2, that was a major shock in Burnley but that was on a night so hot and humid we were knocked out and Harry just put it down to that. There was no great inquest or fuss made. It was simply ah well let’s get on with the next game. So we won the next 7 games and scored 27 goals. That was Harry – just go out and score more than they do. Same with the Cup Final defeat, we lost, but we didn’t play badly, we enjoyed it. There was deep disappointment of course, bound to be, but at the Café Royal in the evening we had a great time – Harry loved his food.

The only time I ever saw an example of his touchline misbehaviour though was during a game at Stoke and Alan Ball senior was manager. I don’t think Harry liked him and something happened to annoy him during the game so he and Alan Ball sat there throwing stones at each other. There was this red grit stone stuff round the perimeter so there they were throwing it at each other. Then there was the time at Reims of course when he ran on the pitch. Harry could not abide cheats or cheating and that’s why he did it. But after the game he was just so delighted and excited we had gone through to the next round, he wasn’t at all bothered or worried about what he had done on the pitch or that the French had been thumping him, throwing bottles at him and jostling him as he was led off.

The only time I ever saw an example of his touchline misbehaviour though was during a game at Stoke and Alan Ball senior was manager. I don’t think Harry liked him and something happened to annoy him during the game so he and Alan Ball sat there throwing stones at each other. There was this red grit stone stuff round the perimeter so there they were throwing it at each other. Then there was the time at Reims of course when he ran on the pitch. Harry could not abide cheats or cheating and that’s why he did it. But after the game he was just so delighted and excited we had gone through to the next round, he wasn’t at all bothered or worried about what he had done on the pitch or that the French had been thumping him, throwing bottles at him and jostling him as he was led off.

As a man manager he was so good. You could relate to him, trust him, you knew it hurt him just as much to drop a player as it was to be dropped. He was never a man to walk past you without a greeting or a word or a conversation. He could never walk past you and blank you or ignore you. He cared about private and personal welfare of players. You knew he was just genuine and honest. So when I had a broken little toe I still wanted to go out and play for him so I cut a small hole in the boot to take the pressure and tightness off and played on with a broken toe.

Jimmy Adamson became coach and by the end of the 60s was making most of the tactical and coaching decisions, if not all of them. He might even have been picking the team but I can’t be sure. Harry certainly did less and less actually on the Gawthorpe training pitches but that of course might have been just as much due to his getting older as anything else. Harry would have been 50 or thereabouts by the end of the 60s. He gradually stopped playing in the 5 a sides that he used to love so much and it became reasonably clear that Jimmy was taking on more and more responsibility. Then when he became General Manager that was the end of his direct involvement in training and team matters though he would often be seen standing watching. He became responsible for scouting and reporting.

He had a great influence on me personally. When I became a manager myself I’d sometimes find myself asking what would Harry have done in such and such a situation, or I’d remember Harry would have done this or that in situations that I found myself in. He taught me that players respond to a manager who makes them feel they are looked after and protected. He showed me that nice guys could win things and that you don’t need to bully players and throw teacups. At our peak he had this knack of making us feel that we could go out and win. He’d simply say just go out and score more than they do. Or if we were losing he would say just make sure you score the next goal and not them. There was always a chance if you could pull one goal back.

If I had to summarise him I’d say simply this. He always got the best out of his players. With just rare exceptions all his players loved to play for him and that was because he tried to do all he could for them. A great man and with his wife Margaret, just a smashing couple.

This article was original published on 16th January 2006, the tenth anniversary of Harry Potts' death.