“Have we got any throat medicine?” I croaked at Mrs T. At times she can display a callousness that it is most unbecoming. Clearly, I was expected to know exactly where the Benylin was. By now it was a rasping cough that went through the chest right down to my knees. This was the downside of being top of the Championship.

“Help,” I croaked pathetically. “I’m not well, you know.”

The look I got was withering and a withering look from Mrs T is not to be sneezed at despite the fact that this was real Man-Cough I was suffering from.

The international break was therefore welcome. I’m not sure I could have taken another top of the table clash had there been one on the following Tuesday. I’m not as young as I used to be.

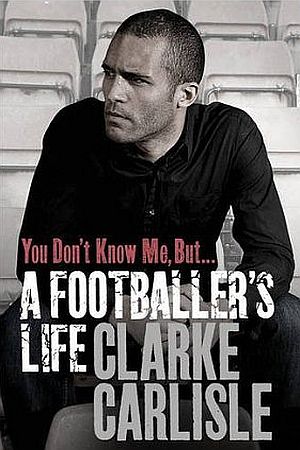

So: I dug out the Clarke Carlisle book I’d bought and was on the pile of books that were waiting for a bit of spare time along with the Clive Cusslers and John Grisholm. The extracts in the Daily Mail had been ‘sensationalist’ to put it mildly. I’d have been disappointed if the whole book had been like that. Fortunately it wasn’t, although Clarke has a fondness for the word sh*t that shines through over and again. He reveals in the book that he does indeed learn a new word every month, but it’s also clear on many pages he has retained the language of the dressing room.

So: I dug out the Clarke Carlisle book I’d bought and was on the pile of books that were waiting for a bit of spare time along with the Clive Cusslers and John Grisholm. The extracts in the Daily Mail had been ‘sensationalist’ to put it mildly. I’d have been disappointed if the whole book had been like that. Fortunately it wasn’t, although Clarke has a fondness for the word sh*t that shines through over and again. He reveals in the book that he does indeed learn a new word every month, but it’s also clear on many pages he has retained the language of the dressing room.

The format of the book is fairly straightforward. It’s the story of his final season in the game after leaving Burnley. It’s part diary, part confessional, and as the story of that year unfolds, at lowly York and Northampton as opposed to Prem games with Burnley, there are flashbacks and anecdotes that skim the story of his whole career and experiences with various managers. His wage has plummeted, although it’s hard to feel truly sympathetic when what he’s getting is still a lot more than my pension. What is also clear is that at the time of writing the book, he had precious little of his previously generous wages left. Being as frank and open as he is about his financial affairs, we are privy to a level of spending that soaked up just about everything he earned so that there was nothing left for any proverbial rainy day.

He reveals that he received an advance of at least £6,500 for his book before he had even finished it and that certainly £6,500 of that advance was spent immediately he got his driving licence back on sorting out car needs because there was nothing in the bank. Oh to be a celebrity writing for one of the BIG publishers, in this case Simon and Schuster with offices in London, New York, Sydney, Toronto and New Delhi. My guy has offices in Skipton and … well just Skipton actually.

In August 2012, he was 32 years old (not that old these days for footballers who take care of themselves) and was facing life on the football scrapheap. A little more than two years after playing in the Premier League he was without a contract, but was still desperate to continue playing. The book is the story of what happened next and reveals a grim truthfulness about footballers who ply their trade away from the glamour of the Prem. In his case it is the story of what happens when a very generous salary suddenly plummets and there are no savings.

At Burnley he had been under the impression that he was part of Eddie Howe’s plans and that a new contract was in the offing. He liked Burnley and like so many players who have played there felt comfortable and happy. The wives had formed a circle of friendship that he had never experienced at any other club. And then there was a shattering U-turn when Eddie Howe called him in and told him he would not be playing for him during the next campaign and his contract would not be renewed at the end of it. He confesses to being almost in tears on the other side of the desk and was so taken aback he didn’t have the wherewithal to react, and just got up and drove home. What made it worse was Howe telling him he didn’t even want him to come back for pre-season training. He could do what he wanted but he would not be required to attend. He was astonished and hurt and – the worst way to leave a club – unwanted. For a while he thought he had a chance of a dual role at the club, as player and some kind of paid role within the ‘Football University’ that was being established at one end of the ground.

He had been ‘wanted’ when he joined Burnley and Steve Cotterill paid him £5,000 a week. He had experienced the wonderful Wembley day and was man of the match. Howe made him redundant and without focus in a world where it was hard to get work and the footballing world would see him ‘on his arse,’ until Garry Mills at York offered him salvation following a loan spell at Preston that ended with the change of manager from Phil Brown to Graham Westley of whom he has little good to say. He says little of Steve Cotterill, unlike Brian Jensen who laid into him, in his book. He says surprisingly little of Owen Coyle, they guy who helped him enjoy his greatest day as a player for Burnley at Wembley; other than from the touchline all he could ever shout was ‘track the runners.’ I smiled at that. That was all I ever heard him shout when I sat behind him during a sparsely attended League Cup game. According to Clarke, Brian Laws said nothing.

He remembered his first day at Burnley and a certain Mr Ade Akinbiyi. He had previous with him and many was the game when he’d nipped, body-checked, shirt-pulled and tripped him so as to wind him up. Now, he was in the boot-room under the stand at Turf Moor dropping off his boots on the first day. The door closed and the room went dark. He turned round, and there were 14 stones of muscle blocking the doorway. They belonged to Ade Akinbiyi. On one occasion it had taken the entire Burnley team to stop Akinbiyi from killing him, he says. Now there he was trapped in the boot room with him. Clarke wondered what to do, pray, or just run. He needn’t have worried as the biggest grin creased Akinbiyi’s face and welcomed him to Burnley.

Much of the book’s content is predictable enough – the nomadic lifestyle of footballers, the pressures on marriage, his suicide attempt and its associated guilt and shame, his battles with drink and Depression. The accounts of these and how the drinking and temptations started in London are in some detail and show just how easy it is to succumb. Today he is on permanent medication to combat the Depression. The account of the recent loss of his driving licence for drinking and being over the limit, is a reminder that his demons are not totally under control and that lapses are always close by. Very recently, failing to take his medication badly affected him and real Depression ensued when there was an inability to face the day until the medication was restored.

He relates the fears suffered by most footballers of insecurity and uncertainty as to where the next job will come from, the trauma and effects of injury, and of course the inevitable tales from the dressing rooms of flare-ups and the pranks that footballers get up to. At this point it’s hard not to suspect that the average mental age of footballers when in a group situation is around 14 years old as Clarke goes into the details of 101 things you can do with the human turd. Ugh! And not just in the communal bath. Put 20 or more footballers together and he suggests the result is something that often resembles a school playground when the object of the day is simply to provoke or put each other down with a snappy one-liner; and nobody was better at that than Robbie Blake.

And that’s before you even mention the football drinking culture that seems to be alive and well, certainly at Burnley in Clarke’s time there. He confesses that the Burnley group contained the most hardened bunch of drinkers he had ever come across. You do wonder just what it is that makes it a badge of honour to become paralytic, or to be last man standing. He shows particular pleasure in relating that a bragging Chris Iwelumo was not so much last man standing, but first man down. Sadly, there does seem to be link between alcohol consumption and level of esteem.

Racism in football forms a strong section, Ferdinand, Terry, Evra and Suarez and all its associated fallout. The PFA Awards night when the PFA employed Reginald D Hunter as the ‘comedian’ is examined in detail, when Hunter destroyed the evening with his racist quips and remarks; to him as a black comedian presumably quite normal and acceptable, but to Carlisle and the majority of the audience, quite toe-curling. But I was coldly unsympathetic. To employ this guy in the first place was folly, in fact beggared belief; you’d have to be totally naïve not to have any idea of what his humour would be.

There are huge insights into the manic nature of his final 12 months as a player, the juggling of doing several roles at once, PFA chairman, media pundit, documentary maker, writer, student taking a media course, and Northampton footballer of course, and most of the time without his driving licence and using trains to get around with a taxi to the station at ungodly hour when most of us are still in bed.

Like many footballers under stress he then found it a release and escape to get onto the field for 90 minutes; football providing him with the opportunity to ‘feel glorious for 90 minutes.’ For many players it is this that enables them to play a blinder when off the field they are going through hell. And even with this manic final 12 months he still fittingly makes it with Northampton to a play-off final. Sadly he had a poor game and Bradford strolled through the game winning 5–0. It is after that that he called it a day; still uncertain what the future held other than an ITV Brazil World Cup contract. His previous Wembley appearance with Burnley and his towering performance that day get scant attention.

Of course it’s the Burnley bits I looked for. What was Coyle really like? What were the players’ opinions when he left? What was his secret? How did he motivate them to achieve the impossible? What was it like in those memorable League Cup games? What was that whole season like? There are few answers.

What was the reaction when Brian Laws was appointed? How did it all go wrong after he arrived? What did happen at half-time in the City game? There are no answers but there is one revealing story that perhaps tells you all you need to know when he ends it by saying: ‘There was far more power in the dressing room than in Brian Laws’ hands.’ If ever one sentence illustrates the impact and inadequacy of his appointment then this must be it. They did things that no other manager in his experience would have allowed. Having said that, it’s a shame such power couldn’t have been directed towards better performances on the pitch when it mattered.

A ‘confessional’ book in which you bare your soul can certainly backfire if you lose sympathy for the author and there are times when this happens. There are things he writes about where I felt tremendous sympathy but others when it seemed that his problems were self-inflicted so that sympathy is replaced by incomprehension. How for example, can anyone who earns such huge sums of money and ends up struggling to make ends meet so quickly, merit sympathy? Surely that’s just irresponsible? How can grown men who drink themselves stupid or behave so badly, wrestling naked in hotel corridors, on ‘away’ weekends merit sympathy? Surely that’s just an inability to grow up. How can players who clearly treated Brian Laws with such disrespect merit sympathy. Surely that’s just abusing a bloody good wage packet and letting supporters and club down. Or am I just being a bit po-faced and headmasterish?

And just who was the ex Burnley team-mate who failed to show up at Brian Jensen’s golf day; someone that he claims is on the edge of oblivion with a mindset that is leading him only one way, and actions that have lost him many good friends; ‘a fantastic guy’ but in denial regarding the problems that Carlisle recognises, having been there himself.

Despite the confessions of all his imperfections and lapses of behaviour, and the accounts of players conduct in general that I found almost cringe-worthy, my admiration for the guy remained. This is a book filled with candour and honesty. He was a Burnley hero but heroes have their imperfections and weaknesses. Footballers lead such an abnormal life, is it any wonder their behaviour can be so off the wall. He had a self-confessed limited talent but made full use of it, stretching it to the limit, so much so that the peak he reached in 2009 provided us all with glory and elation that we will long remember.

In some areas of his personal life and the personal battles that he does his best to control, you want him to succeed and win through and find the post-football career that he so badly wants. And there is certainly one insight that makes you both sympathetic and empathetic. Like so many players before him it’s clear that he loved being at Turf Moor and felt at home. He and his wife Gem met up with old Burnley colleagues in Manchester.

‘Afterwards I had pangs of longing to be back at Burnley. This is abnormal for me. I wander from club to club, making new friends and dropping old ones off with very little emotion. It’s just the way that life as a footballer is. This is the only time that leaving a club has had a lasting impact on me. We loved it there.’

He is not the first, and he won’t be the last. It is one confession that despite all his flaws, will cement his worthy place in Burnley history.