Burnley had survived the 1986/7 season and indeed did get to Wembley in the next one. But until the promotion season of 1991/92 the club lurched along in Division Four in the period we call the ‘wilderness years.’ It was a time of no money and little optimism and much disquiet amongst supporters. There was a clear need for injections of new money, or new directors, or an issue of new shares.

‘I offered to put £250,000 in if there were changes to the board but it fell on stony ground. It was my clear impression then and still is that back then the place was just a cosy drinking club for some of the board members and they were happy for things to stay as they were. I put it in writing to the chairman that I intended to buy shares on the open market and accumulate enough shares to stage a takeover. Eventually there was a big row around the boardroom table and I was accused of going behind their backs. This was nonsense of course. I’d put it in writing to them. Next I was threatened with being voted off the board if I continued on this track. At an AGM, Basil Dearing demanded my resignation. I had no idea that was coming and was unprepared. I responded and replied I would not resign there and then but I’d think about it. Rather than resign and have no influence at all, I decided to stay but stopped buying shares. At least as a board member I’d know what was going on and would retain some influence, however small.

‘The board remained the same but minus Jack Simmons and Basil Dearing who decided he’d had enough of the arguments and aggravation. The drift continued until an awful game at Scarborough that Burnley lost. It was a defeat that brought matters to a head. Supporters were livid by now at the whole sorry state of affairs and the endless decline. Frank Casper resigned. I was in Singapore at the time on business and heard the result on the World Service. Jimmy Mullen took over. They were Casper’s players but Jimmy Mullen achieved promotion in ‘91/92 – joy at last.

|

| The squad training in Russia |

‘At the beginning of that season there was trip to Russia. Doc Iven, who had fled from Russia as a boy, would not go back. He still spoke Russian. The whole trip is imprinted in my head. On the outward journey we were halfway down the runway taking off when suddenly the ‘plane screeched to a halt and had to return to the terminal. The Moscow connecting flight was therefore missed. Dark and raining in Moscow we all gathered in a lounge to wait for the ‘plane to Stavropol. Somebody asked for two volunteers without telling them why. Joe Jakub picked someone to go with him and disappeared without knowing where. To our great merriment when we boarded the next ‘plane we saw them having to load all the baggage into the hold.

‘This ‘plane was an old and very slow turboprop. It would be a three-hour journey we were told. Three and a half hours later we were still in the air so it was me who went into the cockpit to ask where the hell are we, found five people in there, and was told there was still another two hours.

‘Tired and weary we landed in darkness to find power cuts. The hotel was awful and my room was on a floor that was being renovated with builders’ gear everywhere. The players were up in arms at the state of the place and were ready to head straight back home. Frank Teasdale calmed them all down.

‘There was a KGB officer with us all the time. We named him Vodka the Lodger. There was an outcry when the players somehow managed to steal and hide his pistol. Having travelled a bit I knew that it would be a good idea to take jeans and food. Jeans you could trade. The food would make up for what was on offer in the hotel. For some odd reason my room had one of the biggest fridges in it I’d ever seen. It was where the players kept the food they had brought.

‘We played two games. After one of them everyone stayed behind. We waited too and eventually realised they were drawing the grand raffle for the star prize of a car. When it was a police officer that won it and the crowd saw him marching down the steps to collect the keys, there was a near riot. Simple programmes had been printed at each game. At one of them the programme had a picture of the 1959/60 title team, Jimmy McIlroy and Jimmy Adamson and all the rest, and this was supposed to be us.

‘The first game in Stavrapol was a 1-1 draw. So too was the second in Kislovodsk a mountain area some distance away. The road up to this ground was so steep the old, battered coach wouldn’t make it. We all had to get off and walk up. The other route up to the top of the mountain was a cable car. All of us had pockets full of roubles that we had been given but this was Russia in the early 1990s. There was nothing to spend them on until at last we found one shop with queues outside. Bernard Rothwell went in and came out clearly excited. This shop had hundreds of toilet plungers on sale really cheap. There was little else, just hundreds of these things. This we discovered was one of those Russian state controlled shops that most of the time were empty back then with nothing on the shelves, until with no warning stocks of something would arrive. It might be shoes. It might be tins of paint or even food. When that happened the people rushed along regardless of what it was. Of course Bernard was excited. He ran James Hargreaves plumbing merchants in Burnley and because these plungers were so incredibly cheap he had this idea to buy a whole container load and ship them back to Burnley. I managed to talk him out of it.

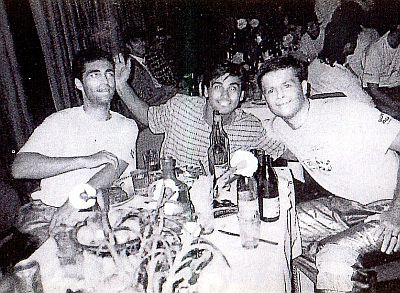

|

| and enjoying Russian hospitality |

‘So, the roubles remained unspent until on the final day in Moscow we saw an impoverished, little, old lady in the street collecting bottles. Vodka the Lodger was sure we’d give all the roubles to him. Instead we handed them all over to the little old lady who was so astonished she ran off with them as fast as she could, probably thinking we’d take them all back, or Vodka the Lodger would confiscate them.

‘After the game in Kislovodsk there was a final celebratory dinner in a very grand Dacha, one of the fine country houses that were the perks of being a politician. The food this time was endless. The ‘plane in which we made the journey back to Moscow was, we were led to believe, the official Stavrapol team plane. I’ve always suspected someone was taking a few backhanders. To our astonishment not only was every seat filled, but people were standing in the aisles and at the front of the ‘plane were crates of chickens.’

I’d arrived at 11 and by now it was past 1.

‘Yes we are prepared for promotion this time having learned from last time,’ said Clive when I asked. He and the board were aware of the statistic that teams that were top at this stage of the season usually went up. Yes they had tried to take Connor Wickham on loan but Sunderland wanted him somewhere where he’d be getting regular games and with Ings and Vokes in such fine form how could they guarantee that.

He touched on the difficulties of setting prices at a realistic level that were affordable but at the same time high enough to pay the bills. The accounts were soon to be published and would show a considerable loss but they had already been made public in an earlier communications exercise. Player wages were under control inasmuch as no player was now on more than £10k a week. But he asked did the supporters that were critical of prices realise that because of the success of the team and the number of wins so far; this meant that the number of player bonus payments had increased dramatically and was now very high. He had read through much of one of the topics on the Clarets Mad message board. It was mostly critical of the Bournemouth game being upgraded to a silver category. Just what was the reasoning behind this people were asking. Decisions on which games to grade as gold or silver, he explained, were made by the management team not just Lee Hoos.

‘I was tempted,’ he said,’ to go on the messageboard myself to say that it was a game that could be attended for just £20 if people bought a flexi-ticket that allows them to pick and choose six games they particularly want to see.’

This was the first of a series of meetings Clive had agreed to; spread out over the coming weeks so that we can not only look back over his time at the club, but also chat about the way things are going this season. It’s clear he thinks that one reason for the good things so far is Sean Dyche’s organisational skills and the board room working well. The financial report won’t be good news but things are under control.

The meeting reached its end and I asked was his role that of general fixer and trouble-shooter. He said nothing but just grinned. Next meeting, sometime before Christmas we agreed, and hopefully still top.